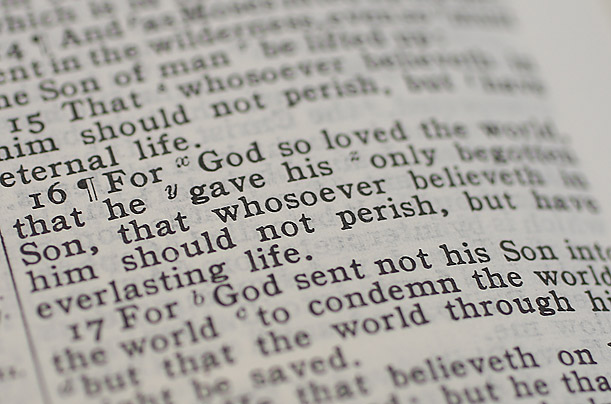

“If we receive the witness of men, the witness of God is greater; for this is the witness of God which He has testified of His Son. 10 He who believes in the Son of God has the witness in himself; he who does not believe G

od has made Him a liar, because he has not believed the testimony that God has given of His Son. 11 And this is the testimony: that God has given us eternal life, and this life is in His Son. 12 He who has the Son has life; he who does not have the Son of God does not have life.” (1 John 5:9-12 NKJV)

The truth laid out in these verses is simple- he who has the Son has life; he who does not believe in the Son of God, does not have life. Salvation comes through Jesus Christ, the one Mediator between God and man (1 Tim 2:5), and no one comes to the Father except through Him (John 14:6).

To believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, then, is manifestly required for salvation. The confession that Jesus is “the Christ, the Son of the living God” is central to the true Christian faith (Matt 16:16).

Yet tragically, many professing Christians deny the Son of God. They do this by embracing Augustinian trinitarianism.

Surely such a statement must seem shocking to many. But consider this- if one believes that the Lord Jesus Christ is the Supreme God, the one God, the Almighty, rather than His Son, then a person does not truly believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.

You see, to believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God requires more than that we simply repeat the words “Son of God”. We must believe what scripture means by the phrase, or it profits us nothing. And scripturally, the Son of God is a distinct individual from the one God, the Supreme God, the Father. To believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God requires us to believe that He is a different person than the God whose Son He is.

Most modern trinitarians simply do not believe this. They are quick to confess their faith that Jesus Christ is not the Father, but the Son of the Father; yet by denying the identity of the one God with the person of the Father, their confession that Christ is the Son of the Father does not equate to a confession of Him as the Son of God.

Rather, they view the one God as the Trinity of three ‘persons’. This Trinity is, in their thinking, the one God, the Supreme God, the Almighty. This person is the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The problems with this anti-scriptural view are manifold; but one of the most alarming is that it severely alters the relationship of the Son with God. Rather than the Son being the Son of God, and a distinct person from Him, this view presents the Son as part of God -a person out of three who is the one God- rather than the Son of God.

This view is still able to maintain the Son’s identity as Son of the Father, since within this “tri-personal God” the ‘person’ of the Son relates to the ‘person’ of the Father as a distinguishable entity, which is begotten by the Father. Thus a Father-Son distinction is maintained, at least at a certain limited level. But since the God is not synonymous with the Father in this view, this in no way equals believing that Christ is the Son of God. This Father-Son distinction is all deemed to be “within God”. Thus the Lord Jesus Christ is confessed to be the Son of the Father, yet denied to be the Son of God.

This all stems from the root problem of denying the historic first article of the Christian faith- that there is “one God, the Father Almighty”, as so many ancient creeds begin. Both the scriptures and the Christians of the first several centuries of church history are clear in stating the identity of the one God with the Father (see here). As Paul the apostle wrote, “For us there is one God, the Father, from Whom are all things” (1 Cor 8:6). And the Lord Jesus Christ defined eternal life, saying “this is eternal life, that they may know You [the Father], the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom You have sent.” (John 17:3 NKJV).

Those then who deny that the one God is the Father Almighty in particular, set themselves not only at odds with classical Christianity as seen in the writings of the church fathers, but more importantly deny a central truth taught by the holy scriptures. In doing so God’s glory is obscured, and the church is harmed, being deprived of important truth. But worse still, such a denial ultimately results in a denial of the basic and necessary Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is the Son of God.

Augustinian trinitarianism, then, or semi-modalism, as I prefer to call it, is not simply some innocuous error. It does not only work against the glory of God and the good of His people- it is, if held sincerely, a damnable denial of the Christian faith, by constituting a denial of Christ Himself. By denying the identity of the Father and the Supreme God, the one God, the Almighty, this heresy makes Jesus Christ out to not truly be the Son of God, but merely a part of His own self. Confessing that Jesus is the Son of the Father is not enough- He must be believed in as the Son of God. “And this is the testimony: that God has given us eternal life, and this life is in His Son. 12 He who has the Son has life; he who does not have the Son of God does not have life.” (1 John 5:9-12 NKJV)

Excellent argument.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello again Andrew,

Normally I would send this query via email, but alas, I was unable to find an email address for you.

Yesterday morning (PDT) I submitted a comment which has yet to be published. I noticed that a comment by Beau Branson (a gent with whom I have had some very productive conversations with), which was submitted after mine, has been published.

As such I must ask: am I currently banned from commenting on your blog?

Grace and peace,

David

augustineh354@gmail.com

LikeLike

Hi David,

I have searched around a bit looking for your comment, but can’t find any trace of it. You certainly aren’t banned, I appreciate your comments. I do have things set so that I need to approve comments, but as I mentioned, I never saw anything about yours.

Perhaps it didn’t go through? I am as confused as you as to what might have happened to it.

LikeLike

OK, I am now confused. My submitted comment from yesterday remains unpublished, by today’s query was immediately published. I suspect some kind of glitch now. As such, I am resubmitting yesterday’s comment below:

Hi Andrew,

Interesting post for sure. I concur with most of what you have written, though I do have some reservations with your label, “Augustinian trinitarianism”. I think that we must carefully clarify exactly what is meant by the phrase. It is a fact that most Trinitarians who identify themselves as heirs to Augustine’s formulations on the Trinity place an unhealthy emphasis on Augustine’s phrase, Trinitas quae Deus est (and its variants – see THIS POST), whilst ignoring his numerous references to a certain supremacy of the Father over the Son (see especially THIS THREAD). I would say that those who do so are not being faithful to Augustine’s full trinitarian thought.

Interestingly enough, many folk identify Homoiousians, Homoians, and adherents of the Monarchy of God the Father as “Arians”, ignoring the fact that all three positions have emphatically denied the THE TWO primary doctrines of Arius and his true followers—i.e. there was a time the Son was not, and his creation out of nothing.

With the above in mind, perhaps it is time to come up with a better label for those trinitarians who embrace only part of Augustine’s reflections on the Trinity, whilst virtually ignoring and/or denying other important elements of his full teaching.

Grace and peace,

David

LikeLike

Hi David,

I’m using “Augustinian Trinitarianism” here to refer to his beliefs as expressed in his books on the Trinity, and in his debate with Maximinus, a Homoian, that God, the one God, is by definition the Trinity. Its this identification of God with the Trinity instead of identifying God as the Father in particular that logically leads to a denial that Christ is the Son of God. Whatever monarchy and causality of the Son by the Father there is in this view, since it is within God, the Trinity, it ultimately doesn’t change this. The problem as I see it is not a lack of affirmation of the monarchy of the Father, but the identification of the one God with the Trinity rather than the Father.

So if you believe I’m using “Augustinian trinitarianism” incorrectly, the thing that would be convincing to me would be evidence that Augustine did not equate God and the Trinity, not merely that Augustine articulated some form of the monarchy of the Father within the Trinity. Given the amount of times Augustine equates God and the Trinity, I think that would be very difficult argument to make.

As an aside, have you read his debate with Maximinus? In it he is presented with an opponent arguing for the strict identity of the one God with the Father, and argues against this view. If you haven’t, I highly recommend it, as it is quite relevant to these discussions: https://contramodalism.com/maximinusvsaugustine/

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike

I haven’t yet gotten through the entirety of the debate with Maximinus, but so far a few observations:

1. Augustine really woke up on the wrong side of the bed that day. Sounds super cranky. Maybe it’s his age at that point.

2. He’s totally gone off the rails with his God=Trinity line at this point. I find this very interesting in terms of assessing Augustine’s development. Lewis Ayres points out that outside the De Trinitate, Augustine still uses “Deus” to refer mostly to the Father, e.g. in his homilies. Also, that affirms the monarchy. So, I used to suspect that maybe De Trinitate was where Augustine was just working through some ideas and experimenting and such, and so maybe we shouldn’t put so much emphasis on that one text. But here he is at the end of his life and he pushes the God=Trinity idea very hard.

I recall that long, long ago I came across something in (I think Book 5) of De Trinitate that made me think Augustine adopted the God=Trinity line just because it, at a certain point, gave him a nice argument against the Arians. I will have to go back and look through again and see how that played out. I suspect he thought that this somehow gave him a good argument, and so continues to push it here when he is talking with a “semi-“Arian.

In any case, sadly, it doesn’t look like this was just an idea he was experimenting with, but actually became very convinced of it. It would be interesting to see what he says about the issue in the Against Maximinus work he wrote after the debate.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Andrew,

Thanks much for your reply. Must keep my comments brief for now, due to lack of ‘free’ time today; but hopefully, will be able to delve more deeply into your response sometime tomorrow.

I own, and have read, volume I/18 of The Works of Saint Augustine – A Translation for the 21st Century, which contians Augustine’s debate with Maximinus; but, it has been almsot 7 years since I did so. Will try to read it again tonight so it is fresh on my mind.

I have a couple of older posts at AF wherein I reference the debate, but keep in mind that those posts were before my extensive research into the Monarchy of God the Father (LINK).

Forgive my brevity for now; I shall return…

Grace and peace,

David

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Andrew,

I have returned…

On 07-10-18, you wrote:

>>I’m using “Augustinian Trinitarianism” here to refer to his beliefs as expressed in his books on the Trinity, and in his debate with Maximinus, a Homoian, that God, the one God, is by definition the Trinity.>>

My initial comments concerning your use of the phrase “Augustinian Trinitarianism” proceeded under the assumption that you were using the phrase with reference to those folk who embraced certain elements of Augustine’s elucidations on the Trinity. Thanks much for the correction of my understanding.

>>Its this identification of God with the Trinity instead of identifying God as the Father in particular that logically leads to a denial that Christ is the Son of God.>>

I think this is an issue on which you and I are currently divided—i.e. though Augustine clearly identifies the Trinity (The Three) as “one God”, he also identifies God the Father as God in a unique sense reserved for Him alone.

>>Whatever monarchy and causality of the Son by the Father there is in this view, since it is within God, the Trinity, it ultimately doesn’t change this. The problem as I see it is not a lack of affirmation of the monarchy of the Father, but the identification of the one God with the Trinity rather than the Father.>>

Don’t think I can agree with the “causality of the Son by the Father” as something that is strictly “within God, the Trinity”. Augustine stated that, “the Father is the beginning (principium) of the whole divinity“; as such, I think one must begin with the Father and not the Trinity when dealing with the issue of causality.

>>So if you believe I’m using “Augustinian trinitarianism” incorrectly, the thing that would be convincing to me would be evidence that Augustine did not equate God and the Trinity, not merely that Augustine articulated some form of the monarchy of the Father within the Trinity.>>

Personally, I distinguish Augustiniaism/Augustinian from Augustine’s actually writings, just as I make a distinction between Calvinism/Calvinistic from what Calvin himself actually wrote. Now that I understand that you are using the phrase “Augustinian trinitarianism” in a restricted sense, I see no need for you to make a change.

>>Given the amount of times Augustine equates God and the Trinity, I think that would be very difficult argument to make.>>

I believe that Augustine did in fact state that the Trinity is “one God”, and did so quite a few times; so, we agree on this. But, I do not believe as you do that this somehow, “logically leads to a denial that Christ is the Son of God.” Augustine, also on numerous occasions, speaks of the Son as being “born of the substance of the Father”; and that the Son is “God from God”, with the first “God” being a reference to the Father, and not the Trinity.

The following from the pen of Dr. Christopher Beeley is noteworthy:

>>The object of the book’s [De Trinitate] overall quest is “the unity of the three, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit (Trin. 1:5). Contrary to how he is often characterized as a theologian, Augustine is not beginning with the divine unity, at least not on the face of it; he is beginning with the three and aiming to discover or show the unity among them.>> (The Unity of Christ, p. 243)

To which I would add, which unity begins with the Father as “the beginning (principium) of the whole divinity“.

Looking forward to your thoughts on my musings.

(After my morning workout, followed by lunch, hope share some thoughts on Augustine’s debate with Maximinus.)

Grace and peace,

David

P.S. Did you personally type up or scan Teske’s translation of the debate, or is there a digital copy available?

LikeLike

Hi David,

Thanks for your thoughts.

I understand that Augustine includes the monarchy of the Father in his trinitarianism, in terms of ascribing to the Father that He is the fountain of divinity, Cause of the Son, etc. But he does not, to my knowledge, equate the one God with the Father in particular in doing this. Rather, his overall scheme, in my understanding at least, is that the one God is the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Then, within the specific relationship of the Father to the Son, we see him include the monarchy of the Father. Yet, this Father-Son relationship is internal to the Trinity, which in his vocabulary is the one God.

To affirm the monarchy of the Father, meaning that the Father is the fountain of divinity and source of the Son and Spirit, is not identical to a belief that the one God is the Father. In Augustine I see the former affirmed and the latter denied. This leaves Augustine, as best as I can tell, basically teaching the same thing that later medieval latin theologians would teach, that the one God is the Trinity, and within that one God there are three persons, and that there is an order among those persons, in which the Father is first as the fountain of divinity whose substance is communicated to the Son and Holy Spirit. IMO this is effectively the monarchy of the Father included in a semi-modalistic understanding of the Trinity.

One of the chief reasons that this distinction between equating the one God with the Father vs the Trinity is important, apart from the monarchy of the Father (although its obviously related), is that if Christ is simply a person out of three in a tripersonal God, then He is not the Son of God. To be the Son of God, when God is defined as the Trinity rather than the Father, would require Him to be the Son of the Trinity, which is not a belief I am aware of anyone holding. On the other hand, when God is identified strictly with the Father (rather than all three persons), then for the Son to be the Son of God is to be the Son of the Father, as He is, and as scripture teaches. Its for this reason that I believe equating the one God with the Trinity necessarily entails a denial that Christ is the Son of God. Someone can believe that internal to the Trinity, Jesus is the Son of the Father, yet, by equating God with the Trinity, not truly believe that He is the Son of God.

What are your thoughts on this? I could be missing something from Augustine that I’m not aware of.

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike

Oh, and as to the copy of the debate, I got it from an acquaintance via pastebin. There was nothing indicating a copyright, so I included it on this site.

LikeLike

Hi,

Do you think that there is a sense which we can call the Three one God, perhaps after the pattern of how ‘the two becomes one flesh’ and ‘the man who joins himself becomes one spirit with him’ and, ‘the heard and soul of the entire multitude was one.’ This wouldn’t be to say that the Three are the one God in the same way the Father is the one God; strictly speaking only he is, but is not the one God as if separated from his Son and Spirit.

LikeLike

Hi,

Not sure if my comment went through, as my browser crashed as I pressed ‘post.’

In any event, I asked if you think there is a sense in which we can call the Three one God, perhaps after the manner of how we can say, “The two became one flesh,” and, “The man who joins himself to the Lord is one spirit with him,” and, “The heard and soul of the entire multitude was one?”

LikeLike

Hi Sean,

I think we can certainly say (as scripture does) that the Father and Son are “one”; by extension this may be said of the Spirit as well. But I don’t see that justifying the language of “one God” being said of all three persons.

Let’s consider the examples you gave briefly; in each of them, there is a unity among a plurality of persons. When that unity is fleshly, they are called one flesh. When the unity is in agreement of heart and mind, they are said to be of one heart and mind. And when there is an agreement/close unity of spirit, they can be called “one spirit”. Seemingly the pattern here then, in the scriptural terminology, is that whatever is the point of unity among multiple persons is spoken of as being “one”; this point of unity is always something each person possesses, in which a likeness/sameness of those subjects is denoted. So if the thing held in unity is ‘x’, then the pattern to describe a unity of persons united on that point would be to call them ‘one x’.

So in assessing the validity of saying “one God” in this manner, we have to ask what’s the point of unity that would be denoted by the term “God”? Is there something possessed by all three persons called “God”?

The short answer is no. The Father and Son share a common ‘Godhood’- but Godhood is different than “God”. A God possesses Godhood; a God is a person who possesses Godhood, Godhood is a quality possessed by a person. This may seem like nit-picking, but the issue here is precision in terminology, so I think its justified. This means that we can say that the Father and Son have “one Godhood”, but they aren’t, at least that I can see, justifiably called “one God”. I skipped over the Holy Spirit here because to my knowledge the Spirit is never called “God” in scripture or described as possessing Godhood.

So while there is a lot of pressure to conform to confessions of the persons of the Trinity being “one God”, as of yet I am unconvinced there is a logical or biblical rationale for doing so. On the contrary, such language seems to usually obscure what scripture is clear in teaching, that the Father in particular is the “one God”.

Anyways, thanks for commenting, and I would be curious to hear what you think of this.

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike

Hi Andrew,

Forgive my somewhat tardy response, but I have been taking in two of my ‘guilty pleasures’ the last couple days—Wimbledon and a StarCraft II WCS tournament.

Yesterday, you wrote:

==I understand that Augustine includes the monarchy of the Father in his trinitarianism, in terms of ascribing to the Father that He is the fountain of divinity, Cause of the Son, etc. But he does not, to my knowledge, equate the one God with the Father in particular in doing this. Rather, his overall scheme, in my understanding at least, is that the one God is the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Then, within the specific relationship of the Father to the Son, we see him include the monarchy of the Father. Yet, this Father-Son relationship is internal to the Trinity, which in his vocabulary is the one God.==

I find nothing in the paragraph that I would currently disagree with.

==To affirm the monarchy of the Father, meaning that the Father is the fountain of divinity and source of the Son and Spirit, is not identical to a belief that the one God is the Father. In Augustine I see the former affirmed and the latter denied.==

I am not aware of an explicit denial in Augustine’s writings that, “the Father is one God”, and/or that he is, “the one God”. I am also not aware of Augustine denying the opening statement of the Nicene Creed: “I/We believe in one God, the Father”.

==This leaves Augustine, as best as I can tell, basically teaching the same thing that later medieval latin theologians would teach, that the one God is the Trinity, and within that one God there are three persons, and that there is an order among those persons, in which the Father is first as the fountain of divinity whose substance is communicated to the Son and Holy Spirit. IMO this is effectively the monarchy of the Father included in a semi-modalistic understanding of the Trinity.==

Before I get to an important selection from Thomas Aquinas, I have a couple of questions: first, what do believe is/are the difference/s between modalism and semi modalism; and second, what do believe is/are the difference/s between semi-modalism and the trinitarianism of the Nicene Creed?

Now to Aquinas; note the following:

>>“I Believe in One God, the Father the Almighty, Maker of Heaven and Earth.”

Among all the truths which the faithful must believe, this is the first— that there is one God. We must see that God means the ruler and provider of all things. He, therefore, believes in God who believes that everything in this world is governed and provided for by Him.>> (Expositio in Symbolum Apostolorum, English trans. by Joseph B. Collins – LINK.)

We know that Aquinas is in a very real sense an heir of Augustine’s reflections on the Trinity; as such, one would think that if Augustine rejected the teaching that the Father is one God, Aquinas’ would be referencing the Trinity, and not the Father in the above paragraph. However, this is not the case. A bit later Aquinas wrote:

>>It is not only necessary for Christians to believe in one God who is the Creator of heaven and earth and of all things; but also they must believe that God is the Father and that Christ is the true Son of God.>>

It seems to me that one can hold that the Father is one God in one sense, but that in another sense the Trinity is one God.

Anyway, looking forward to your response to my questions. I sincerely want to understand with a bit more clarity your take on these important issues.

Grace and peace,

David

LikeLike

Hi Andrew,

Do you think that referring to the Father as Lord obscure the fact that “to us there is only one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom and for whom all things were made?” Or, more generally, what do you make of this passage given that the Father is also Lord?

“Is there something possessed by all three persons called “God”? The short answer is no.”

What if we take saying that the Three are one God is not so much a reference to their common nature or substance, but rather to their having but one authority, and power, namely, the Father’s.

The Father is not – and so is not the one God – without the Son and the Spirit. And they act like extensions of the Father, doing his will because it is the Father’s will (even if they share the same exact will and intentions, they do so, and act upon them, because it is the Father’s will). They act on, participate in, and possess the authority of the Father. So the common possession of all Three that is indicated by calling them one God would be the same will and power, or name. It might, as I think it would, presuppose them having the same essence, but it is not the essence that is so much indicated by saying that they are one God.

(“I am sending my angel ahead of you. You must listen to him for he will not forgive any of your rebellious strife, since my Name is in him,” and “Father protect that on account of your Name, which you have given me,” and, “Baptize them in the Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.”)

Maybe we could express it this way: all three possess the name and power of Yahweh, in virtue of being the Son and Spirit of the Father. On the basis of this all Three could be said to be one God. And yet saying this points back to the more fundamental truth that, strictly speaking, the Father is the one God, whose power and name the Two share in. (First, and most properly, or most strictly speaking, the Father is the one God, and the Two are by extension on account of having the power or name of the Father.)

I suppose that one could say the Son possesses the authority of the Father (“all authority in heaven and earth”) except with regard to himself (“I do nothing of my own, but what I see my Father do”). But given that the Son qua God, anyway, never has his will frustrated, is never denied anything he wills by the Father for the sake of the Father’s will, it seems the “except with regard to himself” exception is not of too much importance; at least, I don’t think *it* would undermine the suggestion I make above. Something else may, but not that. The “except with regard to himself” exception is merely an artifact or perhaps another way of saying that the Son derives his authority and possession of the Father’s name from the Father. But, if he really derives *it* and not just something like *it* we have something common between them other than essence or substance.

What do you make of his suggestion?

Also, this post deals with a similar theme: https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2018/07/12/the-neglected-doctrine-of-the-monarchy-of-the-father; perhaps you would be interested in it, or at least the comments below.

Take care,

Sean

LikeLike

Hi David,

//I am not aware of an explicit denial in Augustine’s writings that, “the Father is one God”, and/or that he is, “the one God”. I am also not aware of Augustine denying the opening statement of the Nicene Creed: “I/We believe in one God, the Father”.//

I am not aware of a direct statement by Augustine saying that the one God is not the Father in particular, but he argues in contradistinction to that that the one God is the Trinity, which implies that he understood the one God is the Trinity and not the Father in particular, as per his debate with Maximinus.

//Before I get to an important selection from Thomas Aquinas, I have a couple of questions: first, what do believe is/are the difference/s between modalism and semi modalism; and second, what do believe is/are the difference/s between semi-modalism and the trinitarianism of the Nicene Creed?//

To sum up each:

Nicene trinitarianism says there is one God, the Father Almighty, and one only-begotten Son of God, Who shares the same generic essence with His Father, and one Holy Spirit; these are three distinct individuals.

Modalism says there is one God who is one individual who chooses to economically manifest himself at different times as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Semi-modalism says that the one God is one individual who is ontologically three persons of Father, Son, and Spirit. From there there is considerably more variety depending on who you talk to, ranging from a breakdown of the relationship between those persons are one defined by ontologically causality of the Son and Spirit from the Father, to a mere economic choice among those three persons to effectively role-play as Father, Son, and Spirit.

Everyone agrees that the one God is an individual person, the question is that person’s identity. Is it the Father, as per Nicea? Is it all three persons, at different times, according to the will of this individual, as per modalism? Or is it all three persons in a constant fixed state of ontological relation to one another, as per semi-modalism?

A Cappodocian view of consubstantiality may allow for one to affirm a Nicene view while saying that the Father, Son, and Spirit are “one God” in respect to a shared metaphysical essence, but this other meaning of the phrase “one God” isn’t dealing with the identity of a the person of the one God. So sure, someone can understand the person of the one God to be the Father and understand there to be another usage of that phrase in reference to a shared essence, but that doesn’t effect the argument I’m making with this article, because the question ultimately hinges on the personal identity of the one God. Non-personal uses of the phrase are then only tangentially relevant.

I am, btw, seriously impressed with the Aquinas quotes. However, that doesn’t justify Augustine simply by way of dependence. For Augustine, the person of the one God= the Trinity. That means that Jesus Christ relates to that one God as a person of Him, rather than as His Son.

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike

Hi Sean,

As I mentioned i n my commentary on the pseudo-athanasian creed, “It continues “17. So likewise the Father is Lord, the Son Lord, and the Holy Spirit Lord; 18. And yet they are not three Lords but one Lord.” I am unaware of the Holy Spirit being called “Lord” in the scriptures. That the Son is Lord, and the Father Lord, is abundantly clear. Yet the way that the term is used in the scriptures has a special significance as a title special to the Son, by which His subordinate headship over all creation, while being under the Godhood of the Father, is denoted. Thus 1 Cor 8:6 says “But to us there is but one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we in him; and one Lord Jesus Christ, by whom are all things, and we by him.” (KJV). In this special sense, in which being “Lord” denotes the Son’s subordinate role to the Father in governing the universe, the term cannot be fittingly applied to the Father. However, in a more general term , simply denoting dominion, it may fittingly be applied to the Father as well as the Son. The special sense which belongs to the Son is denoted by Him being called our “one Lord”. This convention is also common in the early church fathers.”

That sums up my understanding of Christ being our “one Lord” as per 1 Cor 8:6. Just as the Father being our one God denotes His being the one Supreme ruler over all things that are from Him, so the Son being our one Lord denotes His subordinate rule over all things that were made through Him. Thus while both the Father and Son are “Lord” and “God”, the phrases “one God” and “one Lord” have a special significance which applies to one person only, the Father, as the one supreme head over the universe being our one God, and His Son being the one subordinate head over the universe our one Lord.

//What if we take saying that the Three are one God is not so much a reference to their common nature or substance, but rather to their having but one authority, and power, namely, the Father’s.//

This means They share one Godhood, but doesn’t justify calling all three persons together one God. A “god” is an individual who possesses dominion. For the three persons to be one God, They would need to be a single individual subject. The unity of dominion can be indicated by saying that They share one Godhood, which I affirm.

Its the difference between a King who shares his authority with his son, the Prince, being said to have one royal authority with his son, which is legitimate since his son shares his own authority, and saying that the king and the prince are for that reason together one king. They aren’t one king, the king is the one king. To call them one king makes them out to not simply share authority but to be the same person.

//They act on, participate in, and possess the authority of the Father. So the common possession of all Three that is indicated by calling them one God would be the same will and power, or name. //

This can be accomplished better by simply saying that They all have one will, one power, and one name. But a god is an individual; thus to say that multiple persons are “one God” seems to unavoidably make them out to be a single individual.

In your thinking then, would there be any impetus to go beyond the language of “one will”, “one power”, etc?

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike

Hi Andrew,

I appreciate the importance of articulations that are not only true, but which are also clear and useful – particularly so when the grasp of so many Triniarians on the doctrine is so tenuous and muddled. (And I don’t exclude myself, not entirely anyway.)

“Is God” seems to be a problematic enough as it is in the present theological climate, apart from concerning ourselves with whether we can predicate “being one God” of the Trinity collectively. For, if you say, “The Son is God,” or, “The Son is our God,” and the “Father is God,” or, “The Father is the one God,” the Trinitarian is almost as likely to think this means the Son is the Father as, say, the Jehovah’s Witness allege. (When I was a Witness, that is what I thought.)

However, if the only opposition to the expression, “The Trinity is one God,” is that it is unclear and prone to lead to treating the Trinity as but one person, I don’t think that suffices to banish it’s use. At least if one keeps in mind the distinct senses of “God” you’ve mentioned before, one will be not prone to see this as saying that the Trinity is but one person.

Better yet, perhaps, is to not use “the Trinity” but rather “the Three” and replace the singular copula with the plural: The Three are one God. I think this more clearly reveals that we are talking about three persons. Sometimes it seems “Trinity” is used unreflectively because of its familiarity so that the Threeness indicated by it is not brought to mind. By saying “Three” this is overcome, at least somewhat.

I would understand “The Three are God,” or, “The Three are one God,” to meant “The Three are one Authority,” and as a shorthand description of “The Three are one Authority in virtue of unity with the Father,” which presupposes their being coessential. (Maybe something like how many a civics or US history book might say, “ ‘We the people’ are the authority behind the federal Constitution.”)

Why then say, “. . . are one God” and not “. . . are one Authority”? Because I think saying the former captures more adequately the fact that being one Authority presupposes that they share divinity: The Three plus Gabriel could not be one Authority, since Gabriel is but a mere creature.

And yet, saying that they are God (i.e. all three have divinity) doesn’t adequately capture what follows from that, namely, that they are one Authority.

And yet, this shorthand description points back to the fact that the Son and Spirit derive their authority, power, and nature from the Father; and thus, to the more fundamental truth that the Father is the one God, most strictly speaking.

They are one God, when taken together, with respect to the created order, on account of their shared divinity and authority; but when taken individually, and absolutely, the Father alone is the one God, since he is fount and source of the divinity and authority of the Son and Spirit and is of a higher rank than Son and Spirit.

Take care,

Sean

LikeLike

Hi Sean,

Thanks for your reply.

I appreciate that we cannot simply ban language on the basis of possible misuse. That would not be the main reason I see for eschewing the language of “the three are one God”.

Rather, its that “one God” is necessarily one individual, in my understanding. That’s because, as I understand it, a “god” is by definition an individual with dominion, and that dominion is deity. So for three to altogether be said to be “one God” seems to be necessarily making Them out to be one individual.

Suppose you have three magistrates acting under the authority of a king. They exercise power he has given them over the country, on his behalf. They co-operate with a joint and shared authority. They can very well be said to have one authority. And each of them can be called “a magistrate”. But together, they are not “one magistrate”, since that language implies that they are a single person, not merely that they share authority.

That’s my concern with the “one God” language being applied to all three persons together in the way you’re suggesting. By definition its saying They are jointly a single person, which of course is unbiblical.

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike

Hi Andrew,

Thanks much for answering my questions. You wrote:

==Semi-modalism says that the one God is one individual who is ontologically three persons of Father, Son, and Spirit. From there there is considerably more variety depending on who you talk to, ranging from a breakdown of the relationship between those persons are one defined by ontologically causality of the Son and Spirit from the Father, to a mere economic choice among those three persons to effectively role-play as Father, Son, and Spirit.==

My understanding of Augustine is that though he terms the Trinity (the Three) “one God”, he does not say that the Trinity (the Three) is “one individual”. Augustine states, “‘the Three are One’, because of one substance”; and, “hath one and the same nature”—not “one individual”.

IMO unus Deus (one God) with reference to the Trinity in Augustine’s mature thought has Deus being used in a qualitative sense. This understanding makes sense of the “God from God’ phraseology—found throughout Augustine’s writings, and, of course, in the Nicene Creed.

With the above in mind, take note of the following:

>>One constant strand of argument throughout the book has been that the Father’s monarchia, his status as principium and fons, is central to Augustine’s Trinitarian theology. The discussions of these central chapters of the book should, however, have also made clear that many things come under the umbrella of asserting the importance of the Father’s status as principium. For Augustine, the Father’s status as principium is eternally exercised through his giving the fullness of divinity to the Son and Spirit such that the unity of God will be eternally found in the mysterious unity of the homoousion.>>(Lewis Ayres, Augustine and the Trinity, p. 248.)

Grace and peace,

David

LikeLike

Hi David,

I know we’ve already interacted quite a bit over this on you blog, so I’ll keep it brief unless you’d like me to elaborate more- I’m happy to do so, but also don’t want to beat a dead horse.

Basically my reason for thinking that in Augustine’s trinitarianism the Trinity is an individual, is that he repeatedly speaks of the Trinity as a person by using singular personal language for the Trinity, etc. This goes hand in hand with him regarding the one God as the Trinity, but even if he never did that, praying to the Trinity, using singular personal language for the Trinity, etc, all heavily implies that for Augustine the Trinity is an individual. Or consider his debate with Maximinus- Augustine doesn’t treat the one God being the Father in particular as common ground, yet insist that in addition all three persons are one God in reference to a shared essence, but argues against the scriptural position that the one God is the Father in particular in favor of identifying the one God -spoken of as if a person- as the Trinity.

And yes, Augustine speaks of the persons being one God in reference to essence at times. But it seems like he seamlessly slips back and forth between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ substance- that is, “substance” as an individual, and “substance” as a generic metaphysical nature. Its this apparent blurring of the line between nature and person that IMO is one of the primary problems with both Augustine’s trinitarianism, and that of the latin tradition following him down to our own time.

In Christ,

Andrew Davis

LikeLike